Part Two: Finding the First Exoplanets

In the last blog entry, I shared an introduction to exoplanets and the search for these distant worlds. The first possible evidence for an exoplanet lies in data collected at the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1917. It’s a spectrum of material orbiting van Maanan’s star (van Maanen 2). This is a solitary white dwarf about 14 light-years away from Earth. That data suggested the existence of an exoplanet orbiting the star. Unfortunately, no such companion has been found in the intervening years. But, the idea was certainly on the minds of astronomers as far back as the early 20th century and they had the means to begin the search.

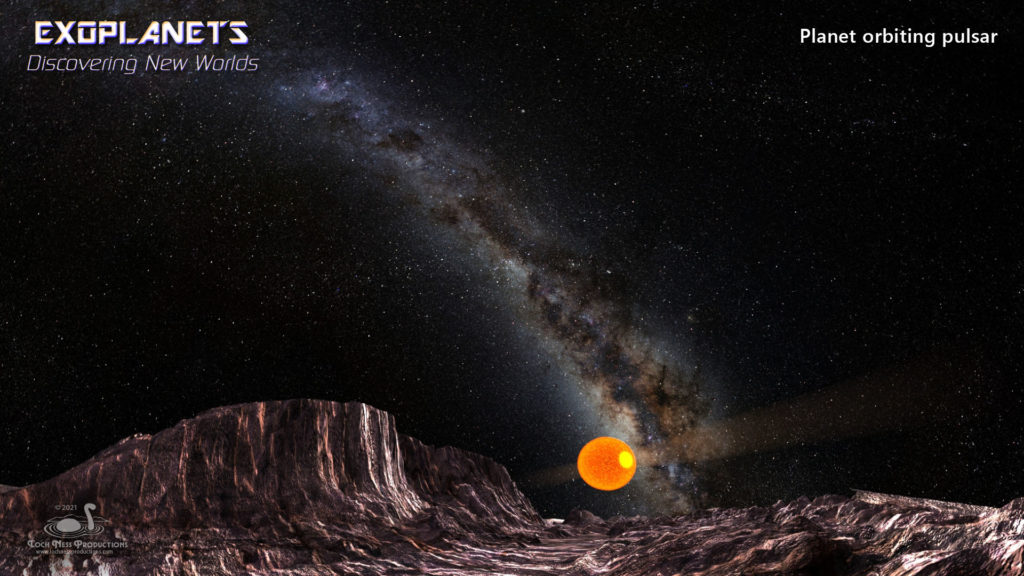

The actual detection and confirmation of distant worlds around other stars had to wait until much later in the 20th Century. One of the most intriguing exoplanet discoveries was among the earliest detections made. It is a multi-planet system, orbiting the pulsar PSR 1257+12. The grouping lies about 2,300 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Virgo. Astronomers Dale Frail and Aleksander Wolszczan found this system using radio telescopes. They were actually measuring pulsation period of the rapidly rotating neutron star at the heart of the system. It was a rather startling discovery. That’s because, at that time, most astronomers thought there was no way a pulsar could have planets.

What about those Pulsar Planets?

In doing the research for our new show, EXOPLANETS – Discovering New Worlds, I had a chance to dig more deeply into the story of these worlds. They managed to survive the explosion of the supernova event that created the pulsar. Now, it’s not considered too likely they would be habitable worlds—since they are scorched by the pulsar’s radiation. But, one of them, PSR B1257 +112 b is a terrestrial-type world. That is, it’s a rocky world with a mass of 0.02 Earth masses. It orbits the pulsar once every 25.3 days. According to NASA’s Exoplanets site, the three worlds around this pulsar have been nicknamed Poltergeist, Phobetor, and Draugr. Those are ghostly characters from literature (including Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Norse legends). This theme fits, since the worlds around the pulsar would be dead, ghost planets.

It’s intriguing to imagine what they might be like, so we “visited” one in our show. After all, as every planetarian knows, audience members have heard of pulsars. So, what better tale to tell than about pulsar planets?

Living with a Pulsar

Conditions around a pulsar are intense. Remember that a pulsar has a tremendously strong magnetic influence on its nearby environment. That’s because a neutron star emitting the pulsar signal has a magnetic field a trillion times stronger than Earth’s field. That creates an incredibly strong radiation environment. In addition, strong magnetic fields generate powerful electrical fields, which have extremely high electrical potentials. The electrical potential contained in just one square meter of space around the Crab Nebula pulsar contains more energy than we’ve ever generated here on Earth.

Future Tourist Traps? Probably Not

So, imagine you’re on a planet that lies within that massive magnetic field or—even worse—it’s in the radiation “beamline”. You’d be standing in a very lethal environment. It’s highly doubtful there’d be any surface water on the planet or much of anything else. In other words, it would very likely be a scorched cinder; not a very safe place to be.

Such a place might be good for a very short visit by explorers someday. Maybe they’ll be searching for artifacts from civilizations that may have inhabited the world in the distant past. Those aren’t the prime motivators in the search for exoplanets—life is. But, it’s interesting to think about what those pulsar planets were like before their parent star went through a metamorphosis of its own.